A tragedy of unimaginable proportions played out in one of our schools this week. Twenty children—innocent beyond belief, filled with hope and potential for the future, and loved deeply by many—were gunned down at random in the sacred halls of an institution where they are supposed to feel protected and nurtured.

Like any parent, I feel the grief of this incident burning a hole in my gut. Like any parent, I can’t help but ask, “what if it had been my child?” My heart is bursting for those who have lost so much. And like any parent, I wonder, “what do we do now?”

The natural reaction is to scour the news for clues to how this happened. What are the societal factors that would allow such a thing to take place? What happened in the shooter’s life to lead him to such a nefarious act of unmitigated evil? What were the warning signs that we all missed that could have been used to prevent this?

The harsh reality is, there is little we could have done. We will learn in the weeks to come, that the shooter showed “all the signs,” and psychologists will talk on the news ad nauseum about the “profile” of a mass killer. Sadly, this information will provide no comfort and no security. There is no way to use this information preventatively because there are thousands, if not millions of other people who will also share this same profile, but will never cross that dark line into horrendous action.

![]() Photo Credit: Royce Bair via Compfight

Photo Credit: Royce Bair via Compfight

We will also, in the weeks and months to come, talk about gun control and school security. We will remove more freedoms, install more cameras, and install more metal detectors. We will teach our children to be afraid of other grown-ups. We will do whatever we can to make our families feel safe again.

I’m all for removing more guns from the world, and we should have more controls in place, but most of these security measures will be driven by fear and incommensurate with the actual level of risk. Consider this passage from another article I wrote on “risk and reality”:

When calculating risk, we tend to use an “availability heuristic”, meaning we judge the likelihood of an event by scanning our mind for any available images or memories of the event happening. News reports of plane crashes and shark attacks are seared into our mind because of the horrific imagery associated with them, and car crashes fade into the background as a seemingly minor event. And so our mind, mistakenly, tells us that because car crashes are less horrific, they are also less likely or less dangerous than plane crashes (a.k.a. “probability neglect”.)

This irrational response to risk pervades every aspect of our society, causing us to accept as normal risks that are very likely but less horrific in our minds (such as car accidents), and yet devote huge amounts of public time, money and resources to preventing more horrific risks, even though their actual likelihood is much lower (terrorist attacks, natural disasters, etc.)

This is why I think now is a time for acceptance, and not irrational fear. The world is a chaotic place. Amidst much peace, beauty and happiness, there is also great tragedy and evil. And this is a part of life.

These acts of evil are very similar to a natural disaster. The earth will occasionally open up and swallow us whole. A tidal wave will occasionally hit our coastlines devastating everything in its path. And every now and then, one of our own will go to great lengths to destroy several fellow human beings—perhaps by flying a plane into a building or bringing an arsenal of guns into a crowded school.

Luckily, these things won’t happen often. But they will happen. And maybe the best that we can do is to cherish what we have with the knowledge that life is fragile and at any moment we “could lose it all.”

![]() Photo Credit: Funkyah via Compfight

Photo Credit: Funkyah via Compfight

But don’t mistake my call for acceptance as a call for inaction. We won’t prevent the next mass killing in the same way we won’t prevent the next earthquake. But we can change as a society. We can become less violent and more loving. We can make the world more safe and more peaceful.

I’m only suggesting that we act from a place of acceptance and love rather than fear and recognize that each of us contributes, by our actions and interactions, to the kind of world we live in. More laws and more metal detectors will only get us so far. What we really need is more love and more understanding.

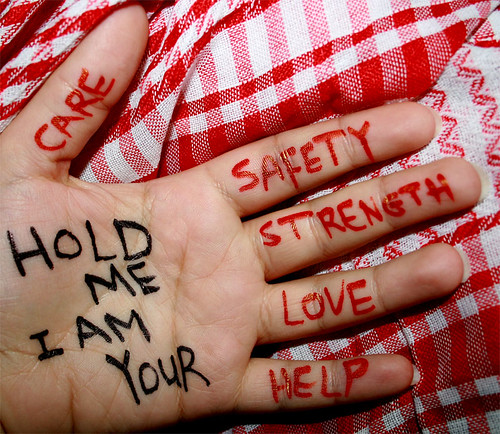

So when people ask, in the face of this horrible tragedy, “what do we do now?”—here is what I propose.

1. Reach more: Can you reach out to someone who is hurting? Can you reach across to someone who is different from you? Can you affect even strangers and passers-by with a simple smile and nod? Can you improve the culture of your organization by improving the style of your own interactions?

2. Listen more: Can you help the people around you feel heard? Can you try to understand the perspective of someone who thinks differently than you? Can you listen for the things that people around you aren’t saying?

3. Love more: Can you practice “unconditional positive regard?” Can you teach your children that most strangers are good? Can you touch more, hug more, and say more kind things? Can you remember that life is short and fragile and cherish those closest to you?

Rather than using guns to create a false feeling of freedom and security, we need to create a more empathic civilization (see video below.) We won’t be truly free until guns are no longer needed.

In the meantime, I’m hugging my children a little tighter this week . . . and hoping that they inherit a more loving world.

by Jeremy McCarthy

Follow the Psychology of Wellbeing on Facebook or @jeremymcc on twitter.

Jeremy – a more realistic perspective is that there will always be troubled people and just perhaps pp can’t help

A decade or so Australia adopted vey stringent gun controls to great effect.

We also have fairly extreme anti smoking measures in place – again it worked.

We have tight banking regulations and we survived the gfc relatively unscathed.

Americans often comment that Australia is over regulated but just perhaps you can’t rely on human behaviour for the good of society.

Oz, I agree with you.